Avian Influenza

With devastating consequences for the poultry industry, farmer’s livelihoods, international trade, and the health of wild birds, avian influenza, also known as ‘bird flu’, has captured the attention of the international community over the years.

Where outbreaks occur in domestic birds, it is often the policy to cull all poultry, whether infected or healthy, to contain the spread of avian influenza. This represents heavy economic losses for farmers and a long-lasting impact on their livelihoods.

Migratory wild birds especially waterfowl, are natural reservoir of avian influenza viruses and they play a role in the spread the viruses across large geographical areas and also becomes victims of the disease.

Avian influenza is also a major concern for public health. Whenever avian influenza viruses circulate in poultry, sporadic cases of avian influenza in humans are sometimes identified.

LINKS TO CODE AND MANUAL

-

Terrestrial Code

-

Terrestrial Manual

What is avian influenza?

Avian influenza is a highly contagious viral disease that affects both domestic and wild birds. Avian influenza viruses have also been isolated, although less frequently, from mammalian species, including humans. This complex disease is caused by viruses divided into multiple subtypes (i.e. H5N1, H5N3, H5N8 etc.) whose genetic characteristics rapidly evolve. The disease occurs worldwide but different subtypes are more prevalent in certain regions than others.

The many strains of avian influenza viruses can generally be classified into two categories according to the severity of the disease in poultry:

- low pathogenicity avian influenza (LPAI) that typically causes little or no clinical signs;

- high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) that can cause severe clinical signs and possible high mortality rates.

What is bird flu?

In the video below, disease expert, David Swayne breaks down the differences between low and high pathogenicity bird flu, as well as the impacts on farmers and consumers.

Transmission and spread

Several factors can contribute to the spread of avian influenza viruses, such as:

Movement of infected birds

Farming and sale (live bird markets)

Wild birds and migratory routes.

In birds, avian influenza viruses are shed in the faeces and respiratory secretions. They can all be spread through direct contact with secretions from infected birds, especially through faeces or through contaminated feed and water. Because of the resistant nature of avian influenza viruses, including their ability to survive for long periods when temperatures are low, they can also be carried on farm equipment and spread easily from farm to farm.

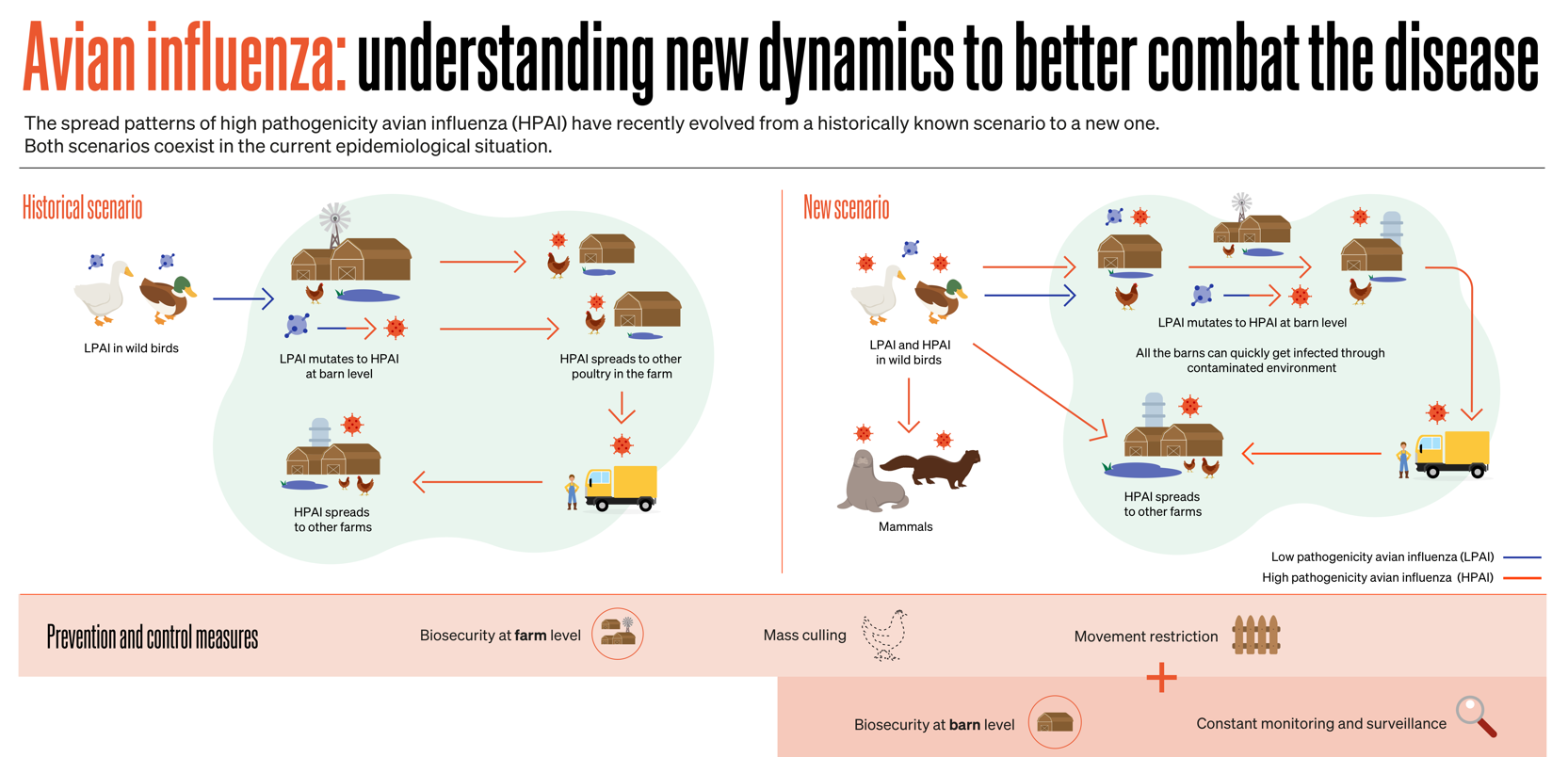

In recent years, the changes in the ecology and epidemiology of specific avian influenza lineages led to infection of numerous wild bird species. Consequently, this facilitated the spread of the virus along established migratory routes, resulting in death of many wild birds, including endangered species, and serving as a source for transmission to poultry and wild mammals.

What role do wild birds play in the spread of avian influenza?

Wild birds mostly, wild aquatic birds can be the reservoir for LPAI viruses, and such infections are not associated with disease or mortality in their hosts. Over long periods of time, some of these LPAI viruses have moved into domestic birds (notably galliform poultry) through direct or indirect exposure followed by adaptation and circulation. Some of those viruses have mutated to become HPAI causing severe losses.

Historically, HPAI viruses have not been transferred back into wild aquatic birds, and wild aquatic birds have not had significant involvement in the spread of HPAI to poultry or other domestic birds. In recent years, the epidemiology of HPAI virus has changed, being endemic in domestic birds in a number of countries causing major outbreaks among domestic but also wild birds worldwide.

The global impact of avian influenza

Economic consequences

Avian influenza can kill entire flocks of birds so this causes devastating losses for the farming sector

Dr. Keith Hamilton

Head of the WOAH Preparedness and Resilience Department

Avian influenza outbreaks can have heavy consequences for the poultry industry, the health of wild birds, farmer’s livelihoods as well as international trade.

Farmers

might experience a high level of mortality in their flocks, with rates often around 50%

Job losses

in developing countries can be significant due to the labour intensive nature of the poultry industry

Healthy birds

are often culled to contain outbreaks, resulting in risks to animal and human welfare, protein wastage and economic impacts

The presence of HPAI

restricts international trade in live birds and poultry meat This can heavily impact national economies

Impact on animal health, including wild birds

With severe mortality rates, avian influenza can heavily impact the health of both poultry and wild birds. Often considered mainly as vectors of the disease, wild birds, including endangered species, are also victims. The consequences of avian influenza on wildlife could potentially lead to a devastating effect on the biodiversity of our ecosystems.

In addition, avian influenza can also cross the species barrier and infect domestic and wild terrestrial and marine mammals.

Public health risk

The transmission of avian influenza from birds to humans is usually sporadic and happens in a specific context. People who are in close and repeated contact with infected birds or heavily contaminated environments are at risk for acquiring avian influenza.

However, due to ongoing circulation of various subtypes, outbreaks of avian influenza continue to be a global public health concern.

For more information: tell us who you are, we will tell you where to go!

You work in the animal health sector and want to help

You are a citizen interested in knowing more

You work in the media and need more information

Situation reports

These reports provide an update of the high pathogenicity avian influenza situation at both global and regional levels, according to the information submitted by countries through the World Animal Health Information System (WOAH-WAHIS).

-

Report, Situation

High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza (HPAI) – Situation Report 57

.pdf – 617 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza (HPAI) – Situation Report 56

.pdf – 660 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza (HPAI) – Situation Report 55

.pdf – 567 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

6 January 2024 to 26 January 2024

.pdf – 583 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

8 December 2023 to 5 January 2024

.pdf – 625 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

17 November – 7 December 2023

.pdf – 549 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

31 October – 16 November 2023

.pdf – 544 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

6 Oct 2023 – 30 Oct 2023

.pdf – 550 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

15 September – 5 October 2023

.pdf – 545 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

25 Aug 2023 – 14 Sep 2023

.pdf – 530 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

14 Jul 2023 – 24 Aug 2023

.pdf – 592 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

23 Jun 2023 – 13 Jul 2023

.pdf – 567 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

02 Jun 2023 – 22 Jun 2023

.pdf – 539 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

5 May 2023 – 1 Jun 2023

.pdf – 540 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

21 Apr 2023 – 4 May 2023

.pdf – 528 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

31 Mar 2023 – 20 Apr 2023

.pdf – 548 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

10 Mar 2023 – 30 Mar 2023

.pdf – 568 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

17 Feb 2023 – 09 Mar 2023

.pdf – 522 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

27 Jan 2023 – 16 Feb 2023

.pdf – 531 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

06 Jan 2023 – 26 Jan 2023

.pdf – 550 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

02 Dec 2022 – 05 Jan 2023

.pdf – 586 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

11 Nov 2022 – 01 Dec 2022

.pdf – 568 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

12 Oct 2022 – 10 Nov 2022

.pdf – 551 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

01 Sep 2022 – 11 Oct 2022

.pdf – 566 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

30 Jun 2022 – 31 Aug 2022

.pdf – 584 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

09 Jun 2022 – 29 Jun 2022

.pdf – 557 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

19 May 2022 – 08 Jun 2022

.pdf – 597 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

28 Apr 2022 – 18 May 2022

.pdf – 569 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

07 April 2022 – 27 Apr 2022

.pdf – 577 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

10 Mar 2022 – 06 Apr 2022

.pdf – 573 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

17 Feb 2022 – 09 Mar 2022

.pdf – 559 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

13 Jan 2022 – 16 Feb 2022

.pdf – 590 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

9 Dec 2021 -12 Jan 2022

.pdf – 610 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

18 Nov 2021 – 08 Dec 2021

.pdf – 600 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

28 Oct 2021 – 17 Nov 2021

.pdf – 593 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

07 Oct 2021 – 27 Oct 2021

.pdf – 563 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

25 Dec 2020 – 14 Jan 2021

.pdf – 307 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

25 Dec 2020 – 14 Jan 2021

.pdf – 307 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

4 Dec 2020 – 24 Dec 2020

.pdf – 304 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

13 Nov 2020 – 3 Dec 2020

.pdf – 313 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

23 Oct 2020 – 12 Nov 2020

.pdf – 313 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

02 Oct 2022 – 22 Oct 2020

.pdf – 314 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

11 Sep 2020 – 1 Oct 2020

.pdf – 319 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

31 Jul 2020 – 20 Aug 2020

.pdf – 338 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

10 Jul 2020 – 30 Jul 2020

.pdf – 313 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

19 Jun 2020 – 9 Jul 2020

.pdf – 321 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

29 May 2020 – 18 Jun 2020

.pdf – 321 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

8 May 2020 – 28 May 2020

.pdf – 321 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

17 Apr 2020 – 7 May 2020

.pdf – 334 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

27 Mar 2020 – 16 Apr 2020

.pdf – 337 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

06 Mar 2020 – 26 Mar 2020

.pdf – 335 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

14 Feb 2020 – 5 Mar 2020

.pdf – 344 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

25 Jan 2020 – 14 Feb 2020

.pdf – 330 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

01 Jan 2020 – 24 Jan 2020

.pdf – 334 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

01 Dec 2019 – 31 Dec 2019

.pdf – 328 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

01 Nov 2019 – 30 Nov 2019

.pdf – 330 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

25 Jan 2020 – 14 Feb 2020

.pdf – 330 KB See the document

Cases of avian influenza in mammals

Situation reports on mammals from Members

-

Report, Situation

H5N1 in a wild red fox in Sweden (August 2023)

.pdf – 173 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

Positive HPAI results in wild mammalian species (UK, August 2023)

.pdf – 60 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

Report of HPAI H5N1 in Chile, April 2023

.pdf – 208 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

HPAI H5N1 Detection in Mink farm in Spain (in Spanish)

.pdf – 448 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

A/H5N1 infections in cats in Poland

.pdf – 132 KB See the document

Avian influenza in cats

-

Factsheet

Q&A: Avian influenza in cats

.pdf – 20 MB See the document

Surveillance and reporting of outbreaks

The first line of defense against avian influenza is the early detection. Putting in place accurate warning systems is thus essential to efficiently prevent and control the disease.

Because of its capacity to rapidly spread across regions, the early detection and timely reporting of cases are key to enable countries to anticipate and get prepared for potential new outbreaks of avian influenza.

Avian influenza is a WOAH-listed disease. As such, national Veterinary Authorities must report:

- Infection with high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses, irrespective of their subtypes, detected in birds (domestic and wild)

- Infection of birds other than poultry, including wild birds, with influenza A viruses of high pathogenicity

- Infection of domestic and captive wild birds with low pathogenicity avian influenza viruses having proven natural transmission to humans associated with severe consequences

When LPAI viruses are detected in wild birds, countries can voluntarily report them through the voluntary report on non-WOAH-Listed diseases in wildlife. In addition, countries may self-declare the absence of high pathogenicity avian influenza from their territory on a voluntary basis.

Prevention of avian influenza at its animal source

Strict biosecurity measures and good hygiene practices are essential to prevent avian influenza outbreaks, because of the resistance of the virus in the environment and its highly contagious nature.

Relevant measures notably include keeping poultry away from contact with wild birds, ensuring good hygiene in poultry housing and equipment and reporting bird illnesses and deaths to the Veterinary Services.

Control strategies and compensation for farmers

When an infection is detected in poultry, a policy of culling infected animals and the ones in close contact is normally used in an effort to rapidly contain, control and eradicate the disease.

Selective elimination of infected poultry, movement restrictions, improved hygiene and biosecurity, and appropriate surveillance should result in a significant decrease of viral contamination of the environment. These measures should be taken whether or not vaccination is part of the overall strategy.

Systems of financial compensation for farmers and producers who have lost their animals as a result of mandatory culling ordered by national Veterinary Authorities vary around the world; unfortunately, they may not exist at all in some countries. The WOAH encourages its Members to develop and propose compensation schemes because they are a key incentive to support early detection and transparent reporting of animal disease occurrences, including avian influenza.

The use of vaccination

Under certain specific conditions, vaccination of poultry may be recommended. However, this measure alone should not be considered a sustainable solution to control avian influenza. It must be used as part of a comprehensive disease control strategy, in addition to other health measures. The vaccines used should comply with the standards described in the WOAH Terrestrial Manual. Vaccination will not affect the high pathogenicity avian influenza status of a free country or zone if surveillance supports the absence of infection.

The decision to set up vaccination plans rests with the Veterinary Authority of each country. It must be based on a risk analysis at regional and national level and in consideration of the international context, potential economic consequences of current outbreaks, and the capacity of the Veterinary Services to conduct an effective vaccination campaign.

Learn More

Have you read?

-

Policy paper, Policy brief

Avian influenza vaccination: why it should not be a barrier to safe trade

.pdf – 283 KB See the document

Insights from WOAH’s 90th General Session and Animal Health Forum

Although WOAH Members have implemented strict preventive and control measures such as movement control, enhanced biosecurity, and stamping out, avian influenza continues to spread. The Animal Health Forum held during WOAH’s 90th General Session convened key stakeholders and the full membership of the Organisation to discuss how to minimise the impacts of avian influenza across sectors. Based on the Technical Item — ’Strategic Challenges in the Global Control of High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza’ presented at the event, participants discussed the impact of the disease, the fitness for purpose of existing prevention and control tools, international trade impact, and the necessity to enhance global coordination. Following the Forum, WOAH issued a policy to action report capturing the discussions and outcomes.

WOAH Members adopted a Resolution which will serve as a basis for shaping future avian influenza control activities, while protecting wildlife, supporting the poultry industry and the continuity of trade. The Resolution notably underscores the importance of Members respecting and implementing WOAH international standards to effectively combat avian influenza.

Learn More

-

Report, Technical

Animal Health Forum on Avian Influenza – Policy to Action: The case of Avian Influenza – Reflections for Change

.pdf – 263 KB See the document -

Report, Technical

A_90SG_8_Technical Item_Strategic challenges in the global control of high pathogenicity avian influenza

.pdf – 978 KB See the document -

Report, Technical

Resolution 28: Strategic Challenges in the Global Control of High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza

.pdf – 217 KB See the document

One Health approach

Because of the potential risk on human health and the far-reaching implications of the disease on the health of wild bird populations, avian influenza should be tackled under a One Health approach. Besides the grave impacts of the virus on poultry, avian influenza can also devastate wild birds populations, threatening the sustainability and biodiversity of our ecosystems.

It is therefore critical that the international community work together across sectors to combat the spread of this disease. WOAH is closely working with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) to monitor the evolution of the disease at the human-animal-environment interface, in line with a One Health approach.

OFFLU: WOAH/FAO global network of expertise on animal influenza

Since its launch in 2005, the OFFLU network has continuously worked to reduce the negative impacts of animal influenza viruses, including avian influenza, by promoting effective collaboration between animal health experts and the human health sector.

The objectives of OFFLU are to:

- exchange scientific data and biological materials (including virus strains) within the network, and to share such information with the wider scientific community

- offer technical advice and veterinary expertise to Members to assist in the prevention, diagnosis, surveillance and control of avian influenza

- collaborate with the WHO to contribute to the early preparation of human vaccines against seasonal flu

- highlight avian influenza research needs, promote their development and ensure coordination

More about OFFLU

Learn More

-

Report

OFFLU Annual Report 2022

.pdf – 205 KB See the document

WOAH global scientific network

Through its global network of more than 300 Reference Laboratories and Collaborating Centres (collectively, ‘Reference Centres‘) the WOAH provides policy advice, strategy design and technical assistance for the diagnosis and control of avian influenza.

Centres of expertise and standardisation of diagnostic methods, their goal is to provide the required technical and scientific expertise and to form opinions regarding the monitoring, control, and eradication of these viruses.

They also propose scientific and technical training for Members and coordinate scientific and technical studies in collaboration with other laboratories and organisations.

The resources on avian influenza found here, developed by WOAH and our partners, are freely accessible and available to everyone for downloading and distribution.

Understanding avian influenza

Learn more about how avian influenza threatens wild birds

Learn more

-

Infographic

Understanding avian influenza

.pdf – 41 KB See the document -

Factsheet

Q&A: Avian influenza in cats

.pdf – 20 MB See the document -

.pdf – 968 KB See the document

Find out what you can do to tackle avian influenza

-

.pdf – 46 KB See the document

-

.pdf – 50 KB See the document

-

.pdf – 77 KB See the document

Learn more with our key publications

On human infections

-

.pdf – 203 KB See the document

-

Publication, Co-Publication

Human infection with Influenza A(H3N8), China

.pdf – 443 KB See the document

On wildlife

Epidemiological archives

-

Infographic

Poster – H5N8 and spread through migratory birds

.pdf – 25 MB See the document -

Infographic

Poster – Global dynamics of HPAI

.pdf – 4 MB See the document

Avian influenza Q & A

Regular global situation reports are developed by WOAH experts, based on the data reported by countries through the World Animal Health Information System (WAHIS). They are publicly available:

Consult the latest situation report

Access WAHIS for latest information

While it is likely that international trade, farming practices and migratory wild birds have contributed to the spread of avian influenza, the current wide range of avian influenza subtypes circulating shows an ever-evolving complexity in both virus genetics and spatiotemporal distribution. This might be explained by multiple reassortments with low pathogenicity viruses circulating in wild birds.

The dynamic of the spread of avian influenza viruses is complex and difficult to predict. However, the data received by the WOAH over the last 15 years helps to reveal a seasonal pattern: the number of outbreaks of HPAI usually is lowest in September, begins to rise in October, and peaks in February. Several factors can influence this dynamic, such as the wild bird migration pattern, unregulated trade, farming systems, biosecurity and immunity status.

At local level, as the avian influenza viruses can survive for long periods in the environment, they can be easily transmitted from farm to farm by the movement of infected animals, as well as contaminated boots, vehicles and equipment if the adequate biosecurity measures are not implemented. During the Northern Hemisphere winter, the wild bird movements may increase, and lower temperatures may facilitate the environmental survival of avian influenza viruses, increasing exposure of infection in poultry. Additionally, the mixing of wild birds from different geographic origins during migration can increase the risk of virus spread and genetic reassortment resulting in changes in viral properties.

Sustaining veterinary activities amid the COVID-19 pandemic is essential in avoiding the detrimental impacts of other diseases, including animal diseases, which could further exacerbate the current health and socio-economic crises.

Despite the challenging context, Veterinary Authorities in the affected countries have responded to contain AI outbreaks in poultry with control measures, heightened surveillance, and biosecurity recommendations to poultry owners.

The transmission of avian influenza from birds to humans is rare and usually occurs when there is close contact with infected birds or heavily contaminated environments. Indeed, between 2005 and 2020, 246 million poultry died or were culled because of avian influenza. In the same period of time, human have occasionally been infected with subtypes H5N1 (around 850 cases reported), H7N9 (around 1,500 cases reported), H5N6 (around 50 cases reported) and sporadic cases have been reported with subtypes H7N7 and H9N2.

Following the evolution of the global situation, the WHO Global Influenza programme regularly releases risk assessments on influenzas at the human-animal interface.

Moreover, there is no evidence to suggest that the consumption of poultry meat or eggs could transmit the AI virus to humans. However, as a general precautionary measure, animals that have been culled as a result of the implementation of control measures in response to an avian influenza outbreak should not enter the human food and animal feed chain.

It is essential for poultry farmers to maintain biosecurity practices to prevent the introduction of the virus. Some of these measures include:

– prevent contact between poultry and wild birds

– minimise movements around poultry enclosures

– maintain strict control over access to flocks by vehicles, people and equipment; clean and disinfect animal housing and equipment.

– avoid the introduction of birds of unknown disease status

– report any suspicious case (dead or alive) to the veterinary authorities

– ensure appropriate disposal of manure, litter and dead animals

– vaccinate animals, where appropriate.

As soon as detected or suspected, avian influenza should be brought to the attention of Veterinary Authorities in accordance with national regulations. In an effort of surveillance and transparency, these authorities are required to timely report of high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses detected in both poultry and non-poultry species including wild birds, and low pathogenicity avian influenza viruses that have proven natural transmission to humans with severe consequences to the World Organisation for Animal Health. In addition, LPAI viruses in wild birds can be reported on a voluntary basis, through the voluntary report on non WOAH-Listed diseases in wildlife.

Notifying the disease occurrences helps to better monitor, understand and control it.

To support countries in the fight against this disease, WOAH developed international standards on avian influenza, which provide the framework for the implementation of effective surveillance and control measures.

As part of the OFFLU network (WOAH/FAO) of experts on animal influenzas, WOAH and its partners work together to assess the risks of avian influenza viruses and provide the needed guidance and recommendations to the international community.

Additionally, the World Animal Health Information System (WAHIS) provides a window on the disease situation worldwide. Through its online platform, the system disseminates information about avian influenza outbreaks and sends alerts on events in real time. This allows the international community to follow the evolution of the virus and, therefore, to implement appropriate and timely responses.

Avian influenza in cats

Avian influenza, also known as bird flu, is a highly contagious viral disease that affects domestic and wild birds. The disease has also been detected, on rare occasions, in mammals, including humans. Beyond its impacts on animal health, the disease has devastating effects on the poultry industry, threatening workers’ livelihoods, food security and international trade.

Avian influenza can easily spread through:

– secretions and excretions from infected birds, especially faeces

– contaminated feed and water (in farms or live birds market)

– contact with contaminated footwear, vehicles and equipment

– cross-border movements of birds, including wild birds migration and illegal trade

Avian influenza viruses are classified into subtypes based on two surface proteins, the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). For example, a virus that has HA 7 protein and NA 9 protein is designated as subtype H7N9. At least 16 hemagglutinins (H1 to H16), and 9 neuraminidases (N1 to N9) subtypes have been found in viruses from birds, while two additional HA and NA types have been identified only in bats.

While it primarily affects poultry and wild birds, avian influenza can occasionally be transmitted to mammals, including cats. Cats are unusual hosts of avian influenza.

Exposure to infected wild birds or poultry, or associated food products, are modes of infection for cats. However, further studies are required to increase our understanding of this question.

When infected, cats can show a range of clinical signs, including listlessness, loss of appetite, severe depression, fever, dyspnoea (difficulty breathing), neurological disease, respiratory and enteric signs, jaundice, and death. These signs are expected to develop within a few days of exposure to the virus. As with many viral infections, some cats may only show mild signs.

Yes, some cats have died from avian influenza.

The severity of the disease in cats can vary widely depending on the specific strain of avian influenza involved and the individual cat’s health and immune status. Some infected cats may only show mild symptoms or even be asymptomatic, while others can develop severe respiratory distress and other complications that may lead to death.

‘Cat flu’ is a common term used to describe disease in cats characterized by signs like a common cold in humans (e.g., runny eyes, sore mouth or throat, dribbling, sneezing, fever). It can be caused by various viruses (calicivirus, herpes virus) or bacteria (bordetella bronchiseptica, chlamydia felis). Vaccines to ‘cat flu’ are commonly available from veterinarians; they provide protection, but they are not 100% effective.

On the other hand, influenza infection in cats is not the same as cat flu – it relates to an infection of a cat with an influenza virus. No commercially available influenza vaccines are available for cats.

Cats have been known to be infected with several other subtypes and strains of influenza viruses. Usually, infection is subclinical or only causes mild disease. However, the severity of disease may be exacerbated by stress or other chronic illness. Factors that determine species susceptibility to different influenza viruses are not well understood and require further research.

Cats are not significant epidemiological vectors of avian influenza to humans or other animals. While it’s unlikely that people would catch avian influenza through contact with an infected wild, stray, feral, or domestic cat, it is possible—especially if there is prolonged and unprotected exposure to an infected animal. Precautions should be taken when handling a sick animal, whether it is a beloved pet or a wild animal.

The risk of transmission of avian influenza from a sick cat to a human is currently very low or negligible.

– Suspected cases of avian influenza in cats should be isolated from other pets, and individuals handling them should wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

– Contact your veterinarian if you suspect your cat is unwell and has been exposed to avian influenza.

– If you experience flu-like symptoms, consult a doctor.

– Where possible avoid direct contact with sick poultry, fallen wild birds, objects with traces of bird droppings, or surfaces or water sources (e.g.: ponds, troughs, lakes) that might be contaminated with saliva, feces, or bodily fluids from birds.

– Upon returning home, ensure that your shoes are kept out of reach of cats.

– After coming home from outdoor areas that may have bird droppings, clean your shoes.

– Disinfect the surface where you placed your shoes.

– Follow regular hygiene practices, such as washing hands with warm water and soap, particularly after returning home and before handling food.

– Maintain hygienic conditions while preparing meals for cats. Avoid feeding cats raw poultry meat, particularly if avian influenza outbreaks are reported in the region.

– Stay informed about the latest announcements from your local authorities. The risk of cats being exposed to avian influenza will be greater if avian influenza is reported in your area.

WOAH is monitoring this event very closely with its Members and scientific network. WOAH is also working with other international Organisations to assess the risk of this event to other animals and for public health.

The Organisation strongly encourages its Members to monitor the occurrence of avian influenza in animals other than birds and to timely inform WOAH through its information system WAHIS.