SARS-CoV-2

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses. SARS-CoV-2, the agent which causes COVID-19 in humans, is a betacoronavirus – a genus that includes several coronaviruses isolated from humans, bats, camels, civets, and other animals. A broad range of mammalian species have demonstrated susceptibility to through experimental infection, and in natural settings, when in close contact with infected humans and with other infected animals. To date, there is not enough scientific evidence to identify the source of SARS-CoV-2 or explain the original transmission route to humans, which may have involved an intermediate host.

LINKS TO CODE AND MANUAL

-

Terrestrial Code

-

Terrestrial Manual

What is SARS-CoV-2?

SARS-CoV-2, the agent that causes COVID-19 in humans, is a betacoronavirus – a genus that includes several coronaviruses

(SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, bat SARS-like CoV, and others) isolated from humans, bats, camels, civets, and other animals. They are called coronaviruses because of their characteristic ‘corona’ (crown) of spike proteins that surround their lipid envelope. Coronavirus infections are common in both animals and humans, and some strains of coronaviruses are zoonotic, meaning they can be transmitted between animals and humans.

Current evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 emerged from an animal source. Genetic sequence data revealed that the closest known relatives of SARS-CoV-2 are coronaviruses circulating in Rhinolophus bat (Horseshoe Bat) populations. There is also evidence that infected animals can transmit the virus to other animals in natural settings through contact, such as mink-to-mink transmission, mink-to-cat transmission, and transmission among populations of white-tailed deer including vertical transmission to their offspring.

Furthermore, there is evidence that, for at least Neovison vison (American minks), close contact with infected animals can represent a potential source of infection in humans. Clinical signs and pathogenesis vary according to the animal species, age, and other factors.

[Page last updated 24 October 2023]

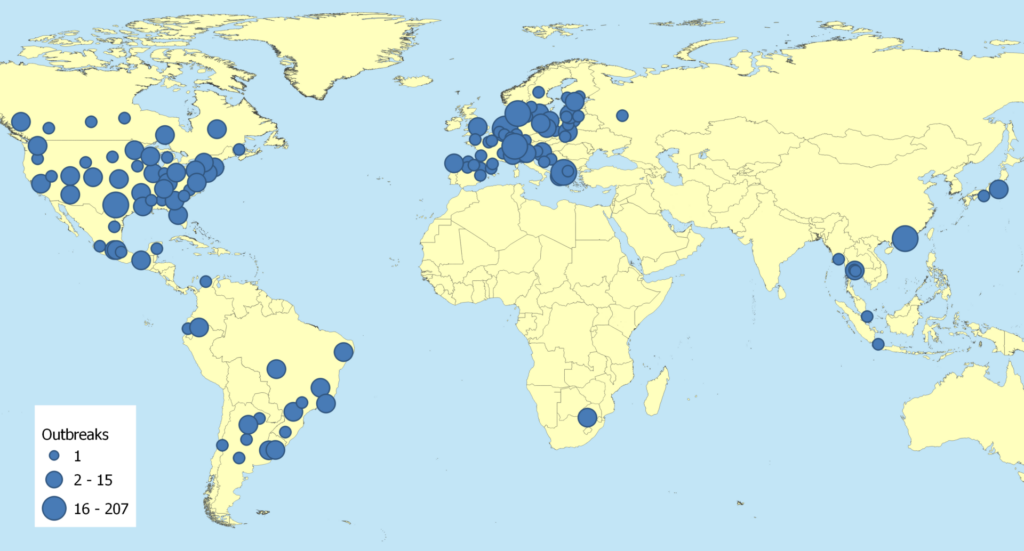

Cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in animals reported to WOAH since March 2020

Number of

outbreaks

775

Number of species

reported

29

Number of countries having reported at least one outbreak

36

Reporting cases of animals infected with SARS-CoV-2 to WOAH

Members keep WOAH updated on any investigations or outcomes of investigations in animals.

Reporting obligations of Members are intended to support:

- Early warning surveillance for animal health events.

- Understanding of dynamic epidemiology for animal health events.

- Understanding of control measures taken in response to events, and their impact.

- Analysis of risks that other Members may be exposed to.

The document below provides a guide to report cases of animals infected with SARS-CoV-2 to WOAH.

-

Guidance

Reporting SARS-CoV-2 to WOAH

.pdf – 353 KB See the document

Situation Reports

-

Report, Situation

SARS CoV-2 in Animals – Situation Report 22

.pdf – 553 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS CoV-2 in Animals – Situation Report 21

.pdf – 551 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS CoV-2 in Animals – Situation Report 20

.pdf – 556 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS CoV-2 in Animals – Situation Report 19

.pdf – 543 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in Animals – Situation Report 18

.pdf – 544 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 17

.pdf – 553 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 16

.pdf – 575 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 15

.pdf – 588 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 14

.pdf – 592 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 13

.pdf – 582 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 12

.pdf – 597 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 11 – 31/03/2022

.pdf – 596 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 10 – 28/02/2022

.pdf – 602 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 9 – 31/01/2022

.pdf – 603 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 8 – 31/12/2021

.pdf – 607 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 7 – 30/11/2021

.pdf – 601 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 6 – 31/10/2021

.pdf – 604 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 5 – 30/09/2021

.pdf – 620 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 4 -31/08/2021

.pdf – 623 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 3 – 31/07/2021

.pdf – 596 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 2 – 30/06/2021

.pdf – 613 KB See the document -

Report, Situation

SARS-CoV-2 in animals – Situation report 1 – 31/05/2021

.pdf – 533 KB See the document

Cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in animals reported to WOAH since March 2020

All reports received through WAHIS can be found on Animal Disease events.

| Member | Species affected | Date of first report | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Cat, dog, puma, tiger, big hairy armadillo | 18/11/2020 | Immediate notification (18/11/2020) Immediate notification (18/03/2021) Follow-up report no. 1 (18/03/2021) Immediate notification (11/01/2022) Follow-up report no. 1 (04/05/2023) |

| Belgium | Cat | 28/03/2020 | Situation update 1 (28/03/2020) |

| Hippopotamus | 13/01/2022 | Situation update 1 (13/01/2022) | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Dog | 03/02/2021 | Immediate notification (03/02/2021) |

| Brazil | Cat and dog | 29/10/2020 | Follow-up report no. 6 (24/08/2022) |

| Canada | Cat and dog | 28/10/2020 | Situation update 1 (28/10/2020) Situation update 2 (21/12/2020) Situation update 3 (10/02/2021) Situation update 4 (09/04/2021) Situation update 5 (02/06/2021) |

| White-tailed deer | 01/12/2021 | Follow-up report no. 3 (07/04/2023) | |

| Mink | 09/12/2020 | Follow-up report no. 11 (21/10/2022) | |

| Lion | 16/12/2022 | Immediate notification (16/12/2022) | |

| Croatia | Cat, dog, lion, lynx | 28/04/2021 | Follow-up report no. 3 (16/11/2021) Follow-up report no.1 (01/12/2021) |

| Chile | Cat | 22/10/2020 | Immediate notification (22/10/2020) |

| Colombia | Lion | 14/12/2021 | Immediate notification (14/12/2021) |

| Denmark | Mink | 17/06/2020 | Situation update 1 (17/06/2020) Situation update 2 (03/07/2020) Situation update 3 (24/08/2020) Situation update 4 (01/10/2020) Situation update 5 (16/10/2020) Situation update 6 (05/11/2020) |

| Tiger | 07/12/2021 | Follow-up report no.1 (21/12/2021) | |

| Estonia | Lion | 22/01/2021 | Situation update 1 (22/01/2021) Follow-up report no. 1 (12/12/2022) |

| Ecuador | Dog | 27/04/2022 | Immediate notification (27/04/2022) |

| Black-headed spider monkey, and common woolly monkey | 20/05/2023 | Immediate notification (20/05/2023) | |

| France | Cat | 02/05/2020 | Situation update 1 (02/05/2020) Situation update 2 (12/05/2020) Situation update 3 (02/04/2021) |

| Mink | 25/11/2020 | Follow-up report no. 1 (06/01/2021) | |

| Finland | Cat and dog | 27/12/2021 | Immediate notification (27/12/2021) Follow-up report no. 1 (18/02/2022) |

| Germany | Cat and dog | 13/05/2020 | Situation update 1 (13/05/2020) Situation update 2 (01/12/2020) |

| Greece | Mink | 16/11/2020 | Situation update 1 (16/11/2020) Situation update 2 (04/12/2020) Follow-up report no. 10 (17/05/2023) |

| Cat | 23/12/2020 | Situation update 1 (23/12/2020) | |

| Hong Kong | Cat and dog | 21/03/2020 | Follow-up report no. 3 (28/03/2020) Follow-up report no. 1 (04/07/2020) Follow-up report no. 1 (04/07/2020) Follow-up report no. 3 (03/09/2020) Follow-up report no. 8 (29/01/2021) Follow-up report n. 1 (17/02/2021) Follow-up report no. 2 (22/02/2022) |

| Hamster | 21/01/2022 | Follow-up report no. 3 (14/02/2022) | |

| Italy | Mink | 30/10/2020 | Situation update 1 (30/10/2020) Situation update 2 (11/11/2020) Situation update 3 (21/11/2020) Follow-up report no. 1 (09/09/2022) Follow-up report no. 28 (05/07/2023) |

| Cat | 09/12/2020 | Situation update 1 (09/12/2020) Follow-up report no. 3 (14/02/2022) | |

| Indonesia | Tiger | 08/09/2021 | Immediate notification (08/09/2021) |

| Japan | Cat, dog, lion | 07/08/2020 | Situation update 1 (07/08/2020) Follow-up report no. 6 (12/10/2021) Follow-up report no. 7 (10/03/2023) |

| Latvia | Cat | 03/02/2021 | Follow-up report no. 1 (31/03/2021) |

| Mink | 16/04/2021 | Follow-up report no. 53 (03/05/2022) | |

| Lithuania | Mink | 30/11/2020 | Follow-up report no. 8 (03/05/2022) |

| Mexico | Dog | 15/12/2020 | Follow-up report no. 6 (05/12/2022) |

| Myanmar | Dog | 06/10/2021 | Immediate notification (06/10/2021) |

| Netherlands | Mink | 26/04/2020 | First report (26/04/2020) Situation update 1 (15/05/2020) Situation update 2 (9/06/2020) Situation update 3 (16/07/2020) Situation update 4 (12/08/2020) Situation update 5 (01/09/2020) Situation update 6 (06/10/2020) Situation update 7 (06/01/2021) |

| Poland | Mink | 03/02/2021 | Immediate notification (08/12/2021) Follow-up report no. 1 (08/12/2021) Follow-up report no 2 (02/12/2021) Immediate notification (08/12/2021) |

| Russia | Cat | 26/05/2020 | Follow-up report no. 1 (20/06/2020) |

| Singapore | Lion | 11/09/2021 | Follow-up report no. 3 (03/13/2021) |

| Slovenia | Ferret | 23/12/2020 | Immediate notification (23/12/2020) Immediate notification (12/01/2022) |

| South Africa | Feline (puma and lion) | 11/08/2020 | Follow up report no. 1 (14/08/2020) Follow-up report no. 1 (03/09/2021) |

| Spain | Cat | 11/05/2020 | Situation update 1 (11/05/2020) Situation update 2 (08/06/2020) |

| Gorilla | 17/06/2022 | Situation update 1 (17/06/2022) | |

| Mink | 16/07/2020 | Situation update 1 (16/07/2020) Situation update 2 (09/04/2021) Follow-up report no. 1 (16/04/2021) Follow-up report no. 1 (16/04/2021) Immediate notification (29/06/2021) Follow-up report no. 1 (14/03/2022) Follow-up report no. 1 (15/03/2022) Follow-up report no. 1 (15/03/2022) Follow-up report no. 1 (15/03/2022) Follow-up report no. 1 (15/03/2022) Follow-up report no. 2 (18/03/2022) Follow-up report no. 1 (18/04/2022) Follow-up report no. 1 (18/04/2022) Follow-up report no. 1 (18/04/2022) Follow-up report no. 2 (18/04/2022) Follow-up report no. 1 (11/05/2022) Follow-up report no. 1 (05/07/2022) | |

| Lion | 21/12/2020 | Situation update 1 (21/12/2020) | |

| Sweden | Mink | 29/10/2020 | Situation update 1 (29/10/2020) Situation update 2 (06/11/2020) Situation update 3 (01/12/2020) Follow-up report no. 4 (27/01/2022) |

| Feline (tiger, lion) | 15/01/2021 | Situation update 1 (15/01/2021) Situation update 2 (25/01/2021) | |

| Switzerland | Cat and dog | 03/12/2020 | Situation update 1 (03/12/2020) Situation update 2 (13/01/2021) Follow-up report no. 32 (25/04/2023) |

| Thailand | Cat and dog | 17/05/2021 | Follow-up report no. 2 (19/07/2021) Immediate notification (22/12/2021) |

| United Kingdom | Cat and dog | 28/07/2020 | Immediate notification (27/07/2020) Immediate notification (24/08/2021) Immediate notification (10/11/2021) Immediate notification (22/12/2022) |

| Tiger | 18/12/2021 | Immediate notification (18/12/2021) | |

| United States of America | Feline (tiger, lion, cat, snow leopard, puma, fishing cat, lynx), dog, mink, gorilla, white-tailed deer, otter, spotted hyenas, South American coati, binturong | 06/04/2020 | Follow-up report no. 26 (27/11/2020) The follow-up to FUR 26 appears as a new WAHIS entry, although it is the same epidemiological event. See: Follow-up report no. 45 (06/06/2023) |

| Mink (wild) | 11/12/2020 | Situation update 1 (11/12/2020) | |

| Uruguay | Cat and dog | 25/05/2021 | Follow-up report no. 1 (07/06/2021) |

Additional Resources

Response to COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2

The unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and the mysteries around this new virus have required innovative approaches to tackle it. At a time when much uncertainty remains and much work still needs to be undertaken to understand how the virus emerged and entered the human population, one certainty abides: collaboration across sectors is key to responding to this crisis.

In the face of the pandemic, WOAH worked intensively with its network of experts and in close contact with its Members to better understand the virus and its emergence and to enhance the capacity of countries to respond to this multifaceted crisis. The pandemic has certainly challenged the activities of Veterinary Services to address critical needs, such as food supply and disease control. Nonetheless, in these times where solidarity is more important than ever, Veterinary Services have played an instrumental role in supporting the response capacity of human health services in various ways, such as through provision of diagnostic capacity.

WOAH’s action through the pandemic

January to March 2020

- IHR Emergency Committee (WOAH as advisor)

- WOAH Ad Hoc Group for COVID-19 at the human-animal interface met for the first time (“informal advisory group”)

- Contribution to WHO R&D roadmap

- Q&A first published

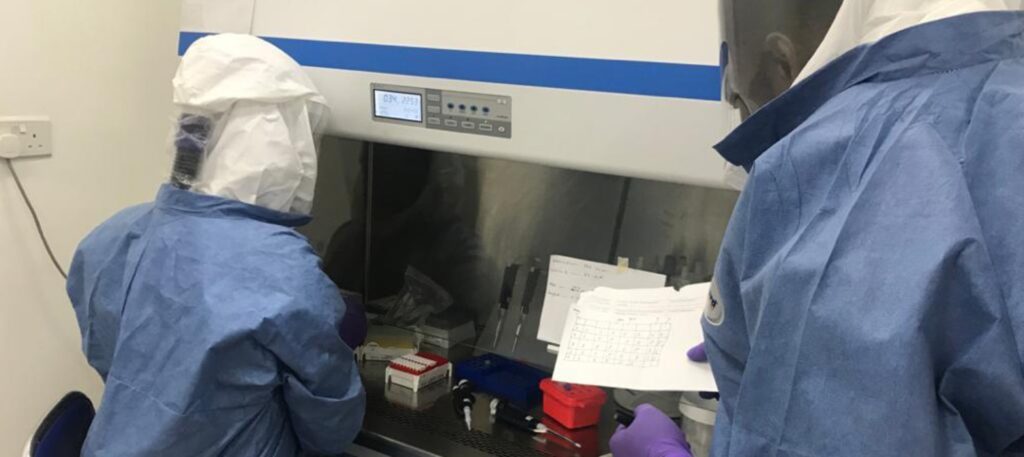

- Guidance on Veterinary Laboratory Support to the Public Health Response for COVID-19

April to June 2020

- WOAH Ad Hoc Group on COVID-19 and Safe Trade in Animals and Animal Products met for the first time

- Statement of the Wildlife Working Group

- Considerations for sampling, testing, and reporting of SARS-CoV-2 in animals

- Considerations on the application of sanitary measures for international trade related to COVID-19

- Technical Factsheet on SARS-CoV-2 infection in animals

- Survey to Members on emerging disease/wildlife

- Special edition of the Bulletin

July to November 2020

- Policy Paper: Prepare for, Prevent & Build Resilience against Health Crises

- After Action Review of WOAH’s response

- Guidelines for Working with Free-Ranging Wild Mammals in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Global Webinar ‘Wildlife Health: Challenges and actions for WOAH – new workstream presented

- Guidelines to work with farmed animals of species susceptible to infection with SARS-CoV-2

WOAH remains committed to timely communicating verified science-based information to the international community as new knowledge comes to light.

A coordinated and scalable response mechanism

WOAH established an Incident Management System to coordinate its response to COVID-19 internally and with external key partners such as the World Health Organization (WHO). Through its mission to set animal health and welfare standards, to inform, and to build capacity, WOAH was fully mobilised to support the work of its partners and to accompany Veterinary Services across the world to address the pandemic.

A multisectoral approach

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided new evidence that a longstanding and sustainable One Health collaboration is needed. From the beginning of the pandemic, existing Tripartite frameworks for emergency management have been used. WOAH participated in the WHO’s International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and WOAH experts have supported the WHO R&D blueprint, which is a global plan that allows the rapid and coordinated activation of research and development activities.

Beyond collaborative research activities, the animal health sector has contributed in various ways towards building a common response to the pandemic in the field. The veterinary profession has shown its commitment to support the work of human health authorities. Whether for the provision of testing capacity by animal health laboratories, through donating essential materials such as personal protective equipment and ventilators, or through direct provision of human resources and expertise, Veterinary Services have greatly contributed to support the international and national response to COVID-19.

Planning ahead

The lasting effects of the pandemic have sent shockwaves into the future, creating greater fragments of uncertainty but also space for innovation. The World Organisation for Animal Health recognises the importance of active preparedness in anticipating and preparing for challenges and opportunities to better adapt its operations and support its membership.

WOAH has been preparing for an event like COVID-19 for several years. Pandemic preparedness and biological threat reduction have been high on the agenda, leading to the establishment of mechanisms such as OFFLU (which would respond to an influenza pandemic of animal origin), a biological threat reduction strategy (supported by two global conferences) and several projects which are supporting capacity building for emergency management and improved sustainability of laboratories.

WOAH has a track record of responding to disease emergence at the human animal interface, having mobilised for H5N1 avian influenza (‘Bird Flu’); Pandemic H1N1; MERS; and H7N9 zoonotic avian influenza. When the WOAH was restructured in January 2020 to notably include foresight and a Preparedness and Resilience Department, it was to take into account global change which is reshaping our environment, in terms of climate, human behaviours, and land use, for example.

WOAH will use foresight to guide its approach – an applied set of methodologies to consider possible future outcomes or “futures”. Foresight is not a means of forecasting or predicting the future. Rather it is a means of acknowledging numerous possible futures, some of which we have a hint of given information available today and allowing the opportunity to be better prepared to address a future made of multiple eventualities. Our collective will and coordinated action remain essential to ensure WOAH and our Members’ Veterinary Services contribute to a better and safer future.

Expert groups and guidance

In the framework of the Incident Management System, several expert ad hoc Expert Groups were established.

Under the leadership of the chair of the Wildlife Working Group, WOAH mobilised an expert group to provide scientific advice and to develop guidelines on a range of topics linked to human-animal-ecosystems interface aspects of COVID-19. These include identifying research priorities, communicating results of ongoing research in animals, developing scientific opinions on the implications of COVID-19 for animal health and veterinary public health, and providing practical guidance for Veterinary Services.

An expert group was also established to assess the risks and implications of COVID-19 for safe trade in animals and animal products.

Our experts speak

Working Group | Wildlife

Ad hoc Group | COVID-19 and safe trade in animals and animal products

Ad hoc Group | COVID-19 and the human-animal interface

Advisory Group | COVID-19 and animal health laboratories

Outputs of expert meetings

- A Coordinated Global Research Roadmap for COVID-19 (WHO Global Research and Innovation Forum).

- Statement of the Wildlife Working Group, April 2020

- Report of Ad hoc Group on COVID-19 and Safe Trade in Animals and Animal Products

- Recommendations from the Netherlands’ Outbreak Management Team on Zoonosis regarding the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from minks and the potential consequences for public health (English only)

Additional resources

-

.pdf – 154 KB See the document

-

.pdf – 259 KB See the document

-

Recommendations

Considerations on monitoring SARS-CoV-2 in animals

.pdf – 325 KB See the document -

.pdf – 491 KB See the document

Wildlife guidance

-

Report, Working Group

Statement on Wildlife Trade and Emerging Zoonotic Diseases

.pdf – 184 KB See the document -

.pdf – 501 KB See the document

Safe trade

-

Recommendations

Considerations on the application of sanitary measures for international trade related to COVID-19

.pdf – 109 KB See the document -

Report, Ad hoc Group

Ad Hoc Group Report of April 2020

.pdf – 380 KB See the document -

Report, Ad hoc Group

Ad Hoc Group Report of Dec 2020-Feb 2021

.pdf – 350 KB See the document

Resources

In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, we have made available several resources to raise awareness on our work and on the contribution of the veterinary profession. Discover them in this section.

Videos

Statements, Declarations, Press releases

-

Published on 19/06/2020

-

Published on 24/04/2020

-

Published on 18/03/2020

-

Statements

Statement on COVID-19 and mink

Published on 12/11/2020

COVID-19: Our Time to Act on Wild Animal Wet Markets

Joint Letter WOAH Director General and WOAH President

Bulletin

Overcoming the impact of COVID-19 on animal welfare: COVID-19 Thematic Platform on Animal Welfare

Countries stories

Bhutan

Veterinarians play a key role in the multisectoral approach to face COVID-19

Germany

Conducting research activities to increase our knowledge on COVID-19 and animals

Ghana

Veterinary laboratories actively support COVID-19 testing of human samples

Indonesia

Veterinary Laboratories in Indonesia Support COVID-19 Testing

Italy

Multidisciplinary collaboration has been crucial to address COVID-19

Spain

Animal health laboratories help break COVID-19 transmission chains in humans

United Arab Emirates

How lessons learned from MERS have benefitted the response to COVID-19

Newsletter

Special issue on COVID-19

Event

Briefing to national Delegates on COVID-19 activities | 7 July 2020

Press contact

[Last updated: 31 January 2022]

COVID-19 is the disease caused by a coronavirus (CoV) named SARS-CoV-2. They are called coronaviruses because of their characteristic ‘corona’ (crown) of spike proteins which surround their lipid envelope. Coronavirus infections are common in both animals and humans, and some strains of coronaviruses are zoonotic, meaning they can be transmitted between animals and humans.

In humans, coronaviruses can cause illness ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (caused by MERS-CoV), and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (caused by SARS-CoV). Detailed investigations have demonstrated that MERS-CoV was transmitted from dromedary camels to humans and SARS-CoV from civets to humans.

In 2019, a new coronavirus was identified as the causative agent of human cases of pneumonia by Chinese Authorities. Rapid international spread of human cases led to COVID-19 being declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). Investigations have not yet identified the origin of the virus. For up-to-date information on the human health situation consult the WHO website.

The current pandemic is being sustained through human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Current evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 emerged from an animal source. Genetic sequence data reveals that the closest known relatives of SARS-CoV-2 are coronaviruses circulating in Rhinolophus bat (Horseshoe Bat) populations. However, to date, there is not enough scientific evidence to identify the source of SARS-CoV-2 or to explain the original route of transmission to humans, which may have involved an intermediate host.

Animal infections with SARS-CoV-2 have been reported in a range of species by a number of countries. Evidence suggests that these infections have been introduced following contact with infected humans.

There is little evidence that animals have infected humans, with the exception of isolated incidents on mink farms where farm workers were in close contact with infected mink.

Yes, a broad range of mammalian species have demonstrated susceptibility to the virus through experimental infection, and in natural settings when in contact with infected humans. There is also evidence that infected animals can transmit the virus to other animals in natural settings through contact, such as mink to mink transmission, mink to cat transmission, and transmission among populations of white-tailed deer including vertical transmission to their offspring.

Infection of animals with SARS-CoV-2 has implications for animal and human health, animal welfare, wildlife conservation, and biomedical research. However, not all species appear to be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2. To date, findings from experimental infection studies show that poultry, swine and cattle are resistant to infection and do not shed the virus.

It is possible that we may see changes in the susceptibility of different animal species to SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease as the virus continues to evolve and new variants emerge.

Up to date information on the susceptibility of different animal species can be found here.

Although a broad range of animal species have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 with varying clinical manifestations, these infections are not the driver of the current COVID-19 pandemic, which is human-to-human transmission.

There is no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infections in animals has a significant impact on human health, animal health, or biodiversity. However, it is sensible to continue to monitor the potential impacts of SARS-CoV-2 at the human-animal-environment interface.

There are concerns about the establishment of SARS-CoV-2 reservoirs in wild or domestic animals, which could pose risks to animal and public health. Although mink and white-tailed deer have been infected at the population level there is no evidence that an animal reservoir has been established. Further studies will be required to assess the possibility for establishment of an animal reservoir and to assess implications for human and animal health.

There is also a possibility for the virus to evolve through animal infections, leading to the emergence of new variants which may behave differently from existing strains.

By monitoring animals for SARS-CoV-2 infections and working closely with other sectors (e.g., the public health sector, wildlife sector, environmental sector) it will be possible to assess implications of animal infections for human and animal health.

More information about the SARS-CoV-2 events in animals reported by countries to WOAH can be found here.

Farmed mink are highly susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection and, in some cases, they have transmitted the virus back to humans. Surveillance findings in Denmark and the Netherlands show that SARS-CoV-2 introduced into mink populations continues to evolve through viral mutation. Viral mutation also happens in human infections, but new mutations may be seen as the virus adapts to a new species. Scientific investigations have confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 infection has been reintroduced from mink to humans.

WOAH acknowledges that such events could have important public health implications. There are concerns that the introduction and circulation of new virus strains in humans could result in modifications of transmissibility or virulence and in decreased treatment and vaccine efficacy. Yet, the full consequences remain unknown, and further investigation is needed to fully understand the impact of these mutations. Read more in WOAH’s Statement on COVID-19 and mink.

As a general good practice, appropriate and effective biosecurity measures should always be applied when people have contact with groups of animals, e.g. on farms, at zoos, in animal shelters, and when handling wildlife. People who are suspected or confirmed to be infected with the COVID-19 virus should avoid close direct contact with animals, including farm, zoo or other captive animals, and wildlife.

Companion animals

There is no evidence that companion animals are playing an epidemiological role in the spread of human infections of SARS-CoV-2. However, as animals and people can both be affected by this virus, it is recommended that people who are suspected or confirmed to be infected with COVID-19 virus avoid close contact with their companion animals and have another member of their household care for them. If they must look after their companion animals, they should maintain good hygiene practices and wear a face mask, if possible. Animals belonging to owners infected with COVID-19 virus should be kept indoors in line with similar lockdown recommendations for humans applicable in the country or area. There is no justification in taking measures which may compromise the welfare of companion animals.

As a general good practice, basic hygiene measures should always be implemented when handling and caring for animals. This includes hand washing before and after being around or handling animals, their food, or supplies, as well as avoiding kissing, being licked by animals, or sharing food.

Farmed animals

Handling farmed animals susceptible to infection with SARS-CoV-2 can carry additional risks when large numbers of animals are kept in close contact. Risk management strategies depend on the species and the circumstances under which the animals live and are cared for. Refer to the specific OIE guidance for further recommendations.

Wildlife

A wide range of mammalian species may be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. WOAH has developed guidelines for people engaged in wildlife work in the field to minimize the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Recent scientific research has shown a high prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection within white-tailed deer populations in North America. This was the first time that the virus has been detected at population levels in wildlife. This discovery requires further research to determine if white-tailed deer could become a reservoir of SARS-CoV-2 and to assess other animal or public health implications. While there is currently no evidence of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from white tailed-deer to humans, there appears to have been multiple introductions of the virus into white-tailed deer populations by humans. People should avoid leaving any human waste or objects in forested areas that may be ingested or touched by wild animals.

Although there is uncertainty about the origin of SARS-CoV-2, in line with WHO recommendations, general hygiene measures should be applied when visiting markets selling live animals, raw meat and/or animal products. These measures include regular hand washing with soap and potable water after touching animals and animal products, as well as avoiding touching eyes, nose or mouth. Precautions should be taken to avoid contact with sick animals, spoiled animal products, other animals present in the market (e.g., stray cats and dogs, rodents, birds, bats) and animal waste or fluids on the soil or surfaces of market facilities. Standard recommendations issued by WHO to prevent spread of the infection amongst humans include regular hand washing, covering mouth and nose with the elbow when coughing and sneezing and avoiding close contact with any person showing symptoms of respiratory illness such as coughing and sneezing. Further recommendations from WHO can be consulted here.

As per general good food hygiene practices, raw meat, milk, or animal products should be handled with care, in particular to avoid potential cross-contamination from uncooked foods to foods which are ready to eat. Meat and meat products, and milk and milk products from healthy livestock that are prepared and served in accordance with good hygiene and food safety principles remain safe to eat.

The Codex Alimentarius Commission has adopted several practical guidelines on how to apply and implement best practices to ensure food safety, which can be consulted on the Codex website.

Veterinary Services should work closely with Public Health authorities and those responsible for wildlife using a One Health approach to share information and cooperate in the response to COVID-19. Close collaboration between animal and public health authorities is imperative to better identify and reduce the impact of this disease.

Close collaboration between several sectors including animal health, public health, wildlife authorities, environment, and academia will be required to better understand the short, mid, and long term implications of SARS-CoV-2 at the human-animal-environment interface.

In some countries, Veterinary Services have supported core functions of the public health response, such as screening and testing of surveillance and diagnostic samples from humans. WOAH’s guidance on Veterinary Laboratory Support to the Public Health Response for COVID-19 is available here. Veterinary clinics in some countries have also supported the public health response by donating essential materials such as personal protective equipment and ventilators.

Veterinary Services should be considered as essential services. National authorities can advocate for this within COVID-19 response plans and operations, to ensure a continuum in the activities related to animal health, animal welfare and veterinary public health, under appropriate protocols.

Veterinary Services should protect animal health and welfare, and consequently public health, by implementing effective risk management measures to prevent the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 between humans and susceptible animals.

Monitoring susceptible animals, such as mink, racoon dogs and white-tailed deer as well as humans in close contact with them, for SARS-CoV-2 infection is important. Active monitoring is recommended as it is difficult to detect early infections in these animals. More information can be found in WOAH’s Statement on monitoring white-tailed deer for SARS-CoV-2.

When a person infected with COVID-19 virus reports being in contact with animals, a joint risk assessment should be conducted by Veterinary and Public Health Services. If a decision is made to test animals as a result of this risk assessment, it is recommended to use RT-PCR to test oral, nasal and/or fecal/rectal samples. The risk assessment may also recommend to carry out a full genome sequencing of the virus isolated from animals. Measures should be taken to avoid contamination of specimens from the environment or by humans.

Animals that have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 should be kept away from unexposed susceptible animals. For further recommendations, refer to WOAH’s guidelines for people working with susceptible farmed animals, as well as with wild mammals in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The infection of animals with SARS-CoV-2 meets WOAH criteria of an emerging disease. Consequently, any case of infection of animals with SARS-CoV-2 should be reported through the World Animal Health Information System (WAHIS) in accordance with WOAH’s Terrestrial Animal Health Code.

Countries are also encouraged to share genetic sequences of SARS-CoV-2 viruses isolated from animals and other research findings with the global health community.

Based on currently available information, and with the support of expert advisory groups, WOAH does not recommend the implementation of any COVID-19 related sanitary measure to the international movement of live animals or animal products without a justifying risk analysis. Evidence-based risk management principles should be applied to international movement of live animals and products from species susceptible to infection with SARS-CoV-2. Evaluation and implementation of risk management for safe trade should follow WOAH’s international Standards, notably for risk analysis, disease prevention and control, trade measures, import/export procedures and veterinary certification). Precautions for packaging materials are not indicated over and above the application of sound principles of environmental sanitation, personal hygiene, and established food hygiene practices.

The report of WOAH’s ad hoc Group on COVID-19 and Safe Trade in Animals and Animal Products can be consulted here, and WOAH’s considerations on the application of sanitary measures for international trade related to COVID-19 can be found here.

WOAH is in contact with its regional and sub regional offices, Delegates of Member Countries, WOAH Wildlife Working Group, as well as FAO and WHO, to gather and share the latest available information. WOAH is closely liaising with its network of experts involved in current investigations on the source of the disease. Rumours and unofficial information are also monitored daily.

WOAH has mobilized several expert groups (‘ad hoc groups’) to provide scientific advice on research priorities, on-going research, and other implications of COVID-19 for animal health and veterinary public health, including risk assessment, management, and communication. Several guidance documents developed by WOAH and its network of experts are available here.

Given the similarities between COVID-19 and the emergence of other zoonotic diseases at the human-animal interface, WOAH is working with its Wildlife Working Group and other partners to develop a longer term work programme which aims to better understand the dynamics and risks around wildlife trade and consumption, with a view to developing strategies to reduce the risk of future disease spillover events.

WOAH is also reviewing lessons learned from COVID-19 to fortify its institutional resilience to international crises. To this end, WOAH has undertaken two after action reviews and has initiated a work stream aimed at building institutional resilience to all threats (irrespective of the cause).